It is Black History Month, and this year’s theme is "African Americans and Labor,” which highlights the ways Black people have influenced labor movements and shaped the workforce in the U.S.

Labor, economics, and the financial health of communities are all intrinsically linked with one another. At Self-Help, we believe in ownership and economic opportunity for all, and labor rights are a key part of making that a reality. That is why

we are honored to recognize Black History Month, the history and influence of Black labor, and how that has shaped and empowered diverse communities across the country.

In this blog post, we will be discussing the history of Black workers in labor movements, the role of HBCUs in Black labor, and the future of Black wealth creation and economic empowerment.

The History & Influence of Black People in Labor Movements

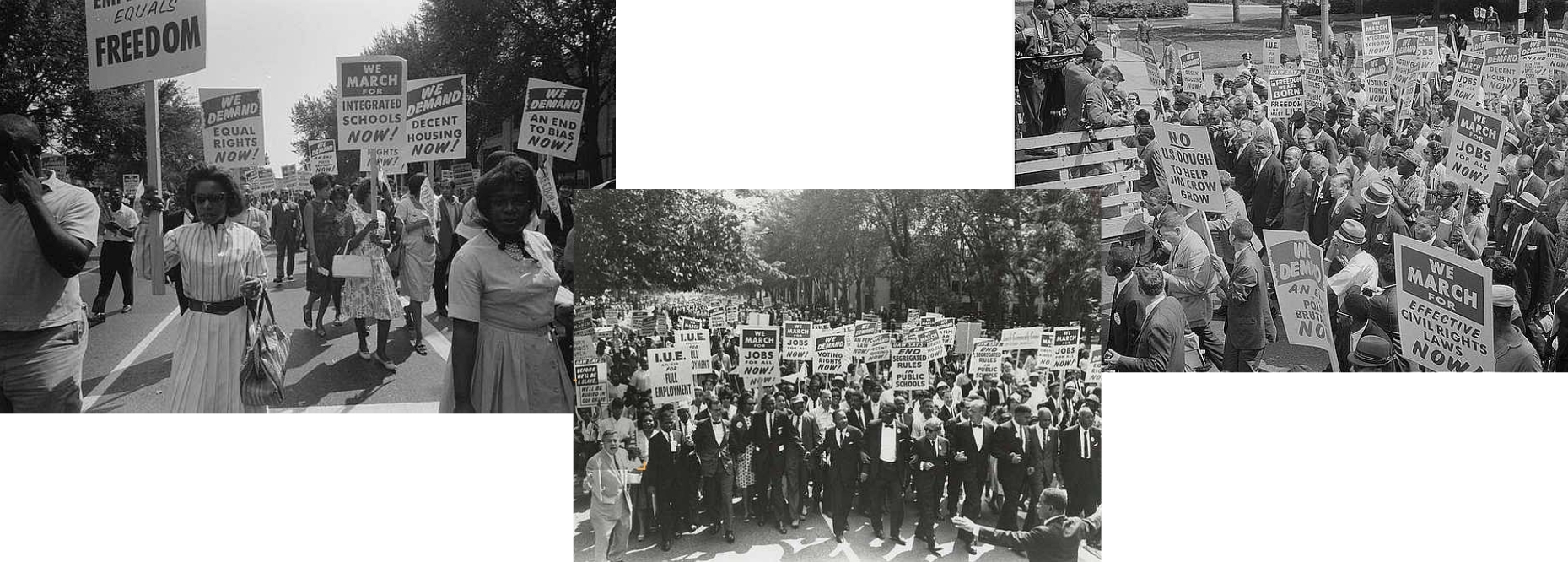

Images from the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963

African Americans have had a crucial role throughout labor movements in America. Due to the history of segregation and racial violence, civil rights were a necessary aspect of truly progressing labor rights. Black workers have had to push for both

civil and labor rights, which has resulted in a huge impact on the trajectory of workers’ rights and on the labor movement as a whole.

The Caulkers Association

In the early 19th century, Black workers dominated certain trades, like caulking. Caulking was of great importance during that time, as ships risked leaking without it. There is documentation of a strike by Black caulkers at the Washington Navy Yard in 1835, which is considered the first strike of federal civilian employees, during which the workers advocated for ten-hour

workdays and pushed to address grievances around lunch-hour regulations. The Caulkers Association was then formed in Baltimore in 1838 as one of the first Black trade unions in the U.S., which set a precedent for the power of unions to collectively bargain and improve working conditions for members.

The Colored National Labor Union

During the Reconstruction era, American trade unions started forming more frequently with both Black and white workers sharing an interest in trade union organizations. While the National Labor Union (NLU) passed a motion claiming that they did not

recognize color during their 1869 convention and that anyone could join the NLU, many local unions ignored this and remained segregated. In addition to prevalent racial tension, this desire to remain segregated is also thought to be due to resentment

between white and Black workers, who saw each other as competitors (when white workers went on strike, Black workers were often employed in their place and vice versa).

Because white workers excluded Black workers from their trade unions, Black workers started organizing independently and established the Colored National Labor Union (CNLU) during a convention that same year, which pursued equal representation for Black people in the workplace. The CNLU was one of the first national Black labor organizations and established

the Bureau of Labor in Washington, D.C. to assist workers of color. The president of the CNLU, Isaac Meyers, believed that white and Black workers should organize together for higher wages and a comfortable standard of living, and he traveled

the country encouraging Black workers to organize and convincing white labor unions to allow nonwhite workers into their organizations.

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

The Pullman Company was the largest employer of African Americans in the late 1800s and early 1900s, purposefully hiring formerly enslaved people to achieve high-quality customer service on the Pullman cars. The sleeping car porters worked long hours

for little pay and endured dehumanization while being expected to provide a wide range of services to ensure passengers had a comfortable trip.

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) was established in 1925

in an attempt to reform these working conditions. They chose civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph as the leader of BSCP since he was not employed by the Pullman Company and could not be fired by them for his actions. Randolph advocated on the

Black porters’ behalf through a number of publications, including a pamphlet called The Pullman Porter, which informed the public about the poor working conditions and wages for the porters and ultimately shifted public opinion.

Due to several factors, it took another twelve years for the American Federation of Labor (AFL) to recognize BSCP as an international charter. When they finally did, BSCP was the first African American union to be chartered by the AFL, and they were

successful in achieving several of their goals including higher wages, fewer hours in the work month, right to hearing before discharge, and reduction of the abuses by service inspectors.

Being a Pullman porter became one of the better paid and socially regarded positions available to Black people, which contributed to the growth of the Black middle class.

Black Labor & Civil Rights in the 20th Century

Between 1915 and 1960, The Great Migration occurred, in which five to six million African

Americans moved north, away from racial violence and toward industrial cities to pursue job opportunities. This had a significant impact on the labor force, as Black workers were needed to contribute to steel, automobile, railroad, and shipbuilding

industries.

During this time, the labor movement and civil rights became intertwined. Black trade unionists linked the priorities and interests of the labor movement with demands for racial equality.

After the AFL and Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) merged in 1955, a Civil Rights Department was created and hundreds of thousands of Black trade unionists became part of an integrated labor movement. Organized labor backed the civil rights movement’s campaigns and mobilized 40,000 union members for the March on Washington for

Jobs and Freedom in 1963, where many Black trade unionists helped plan, organize, and fund Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

The merged AFL-CIO also provided critical lobbying support and testimony for the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which paved the way for the elimination of workplace discrimination and racist voting restrictions.

Civil rights leaders continued pushing for racial justice in addition to labor rights, which cut Black and white poverty rates in half. While the support for unions and anti-discrimination policy has fluctuated over the years, the positive impact

of Black labor on U.S. labor rights and the civil rights movement as a whole is undeniable.

The Role of HBCUs in Black Labor & Civil Rights

Aerial view of North Carolina Central University

The advancement of labor in the U.S. would not be possible without the creation of HBCUs, as these Historically Black Colleges and Universities provided invaluable education and encouraged thought leadership for Black people in the U.S. when they

were being kept out of other educational institutions.

Here are just a few of the ways HBCUs have shifted Black labor and civil rights since the establishment of the first HBCU in 1837:

Creation of leaders: HBCUs initially started as trade schools with a focus on service. As HBCUs upgraded their curriculum to maintain accreditation, a “second curriculum” was established that trained future leaders empowered by education in humanities and social sciences. These fields taught students to think critically about the human condition and transform

their communities. These students created and sustained Black organizations, businesses, and institutions, resulting in generations of Black leaders to champion Black liberation and play critical roles in the civil rights movement.

Cultivation of creativity: HBCUs played a critical role in reasserting and redefining the Black aesthetic in what became known as the Harlem Renaissance. HBCU alumni and faculty who were artists cultivated the creativity of students that created an era of cultural expression through all

kinds of art. The movement brought notice to Black artists, shifted

how other people understood the African American experience, renewed commitment to activism, and influenced future generations of creatives and intellectuals.

Contribution to civil rights: HBCUs have a long history of involvement in the civil rights movement by producing thought leaders that contributed substantially to civil rights leadership and by being breeding grounds for collective action and activism. A few examples include:

Greensboro Four – Four freshmen at North Carolina A&T initiated a peaceful civil rights sit-in protest at a nearby “whites-only” lunch counter in early 1960. This action inspired similar sit-ins across 55 cities in 13 states and led to the store desegregating in July of that same year, with others following suit.

Tougaloo College

– During the civil rights movement, Tougaloo provided a refuge for Freedom Riders and hosted organizers and activists. A group of undergraduates known as “The Tougaloo Nine” also staged sit-ins, most notably

at the Jackson Public Library, leading to its desegregation. Tougaloo College also made sure to find ways for students to complete their studies while participating in the movement.

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

- At Shaw University, the SNCC was co-founded by Ella Baker as a student-led, grassroots organization dedicated to ensuring people of color had the freedom to exercise their rights as citizens. The group served as a catalyst

in the civil rights movement, organizing sit-ins, freedom rides, and the 1963 March on Washington.

Opportunities for advancement in the workforce: Having educational institutions that provided opportunities for Black people to learn and advance in their careers is essential for Black workers and economic mobility. HBCUs

are responsible for a significant percentage of Black graduates with advanced degrees, and they enroll more than twice as many low-income students as non-HBCUs to help create economic mobility for those populations. The mobility rate for HBCUs is nearly double that of all colleges

in the U.S., showing how important HBCUs are for Black workers to prepare for high-paying, in-demand careers.

The Future of Black Wealth Creation & Economic Empowerment

While Black labor and civil rights movements (with the help of HBCUs) have come a long way in helping Black communities to create and maintain wealth and financial stability, huge gaps still remain when compared to the finances and generational

wealth of white peers.

In 2021, the median annual wage for

Black workers was approximately 30 percent lower than white workers. If Black representation matched the Black share of the population across occupations and the racial pay gap was eliminated, McKinsey estimates that Black wages would be $220 billion higher annually. This demonstrates a huge disparity in the capacity for Black communities to build wealth.

According to research from McKinsey, here are some starting points for interventions that can be implemented by us, our workplaces, and HBCUs to help close the wealth gap for Black Americans:

Diversify hiring and promotions in the workplace – Employers should expand where and how they recruit, and hire based on aptitude and skills rather than traditional credentials.

Continue improving labor rights and working conditions

– Giving workers of all industries (especially essential/frontline workers) fair wages, workplace safety, predictable hours, sick leave, and other benefits is essential in supporting workers of all backgrounds in creating a more

economically empowered workforce that feels its value in our society.

Prepare for the future of work

– Many Black workers hold jobs that could be disrupted due to increasing automation and shifting business models. Providing additional training opportunities or sponsoring certifications for employees would give more people the

opportunity to move into more relevant and higher-paying roles.

Help excluded populations enter the job market

– Black Americans have historically been unfairly incarcerated at higher rates. Mentoring or offering jobs to people who have been formerly incarcerated (or any individuals coming from environments where they have been excluded)

would add workers to the economy and give more people opportunities that they have not previously been able to access.

Focus on education

– Some HBCUs are finding ways to improve retention and graduation rates by partnering with organizations to support student success and provide new training programs and research opportunities. It’s important that we encourage

these efforts and support HBCUs as they find more ways to support educational opportunities in Black communities.

Invest in communities

– Actively purchasing from Black-owned businesses re-distributes the flow of wealth into the hands of Black communities and contributes to economic empowerment. Taking a moment to do some research on your upcoming purchases and

buying them from Black-owned businesses is easier than you think and can really make a difference.

Financial education

– Many underserved communities have not had as many opportunities to expand their financial education. It’s important to encourage financial literacy in Black communities to help support the same opportunities for building

wealth and savings as white communities. Self-Help offers financial coaching

free to all members as a resource for people interested in building their confidence and facility with personal finance.

While the disparity in Black wealth creation is still a significant issue, we believe that with continued action by all of us to improve labor conditions, financially support Black communities, and provide opportunities to those who have been

excluded, we can shift the dynamics to create a fairer distribution of wealth.

As part of Self-Help's mission, we are regularly looking for opportunities to support underrepresented communities, including Black workers. Black labor movements and civil rights activism have set the foundation for our work to continue affecting

change and moving us all toward workplaces that work better for everyone.